豐收的構圖及作品賞析

每到水稻收割季節,農家婦女忙得必須背著襁褓的幼嬰到田間工作,甚至只能在阡陌間哺乳幼嬰。

農家收割水稻後將稻桿曝曬數日,然後收集推成草垛,做為日後生活所需。

畫面中加入雞群,不僅是常見情景,另一含義是:雞與家在閩南語裡是同音,有家庭興旺之意,台灣婚嫁必備小雞陪嫁便是此意。

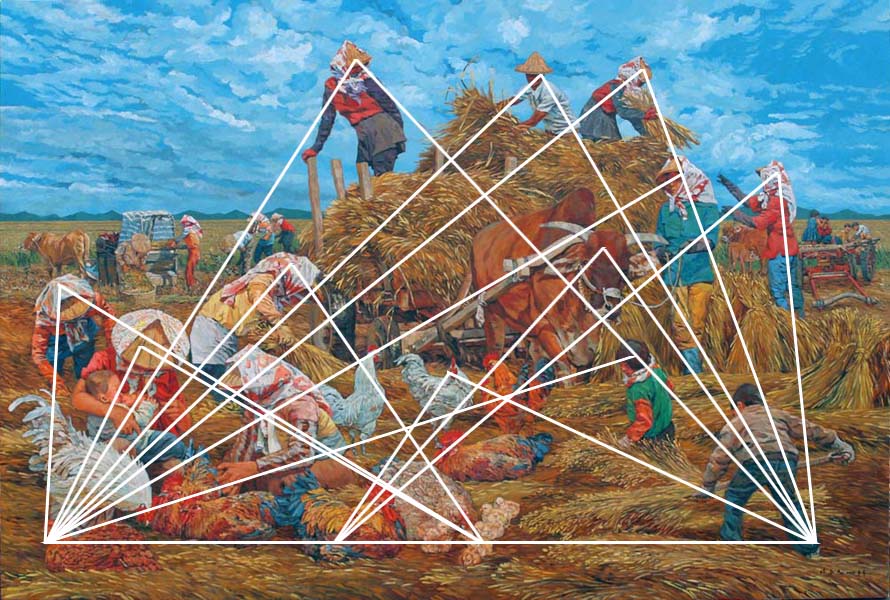

整幅畫用黃金比例與複數三角形構圖,看起來熱鬧且忙碌,又富許多色彩且顏色鮮艷明亮,但無形的涵義則圍繞著“愛”,人物無論收割、堆草以及就學年齡前的孩童都需下田幫忙,都是在為這個家庭做最大努力,哺乳幼嬰的慈母關愛的動作,長輩在旁的寒暄問暖、呵護備至,再再表露這個家庭的期望與未來,在牛車上嬉戲、抓頭蝨的溫馨童趣顯示這個家庭歡樂融融。

而雞群亦富趣味含意:圖左下“求愛”舞動翅膀的妙姿、以及母雞帶著小雞覓食,這不都是“愛”的具體呈現,公雞的啼叫及凝視警戒更暗示這個家庭的雄心與戒慎。

牛車旁的黃牛也是舐犢哺乳的“愛”。

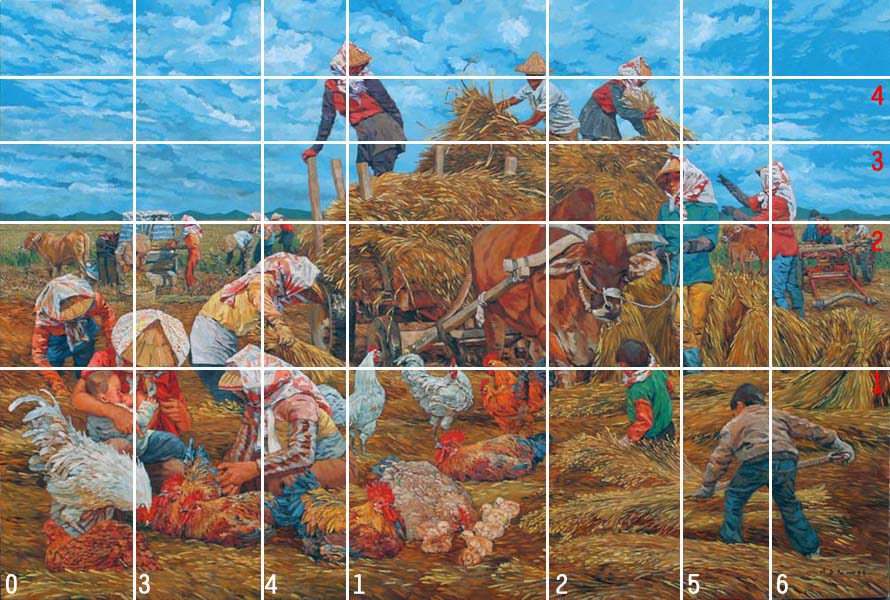

構圖的骨架是採黃金比例分割方式

黃金比例的公式是: 長邊:短邊=(長邊+短邊):長邊

比值是: 長邊:短邊為1:0.618或1.618:1

畫面高度黃金比例分割

1、取總高度的黃金比例短邊做為幫忙剷稻草女孩、襁褓幼嬰、在旁哄幼嬰婦女、公雞群的高度。

2、以幫忙剷稻草女孩、襁褓幼嬰、在旁哄幼嬰婦女、公雞群高度至頂邊的距離取黃金比例短邊做為黃牛及視平線的參考高度。

3、以黃牛及視平線的參考高度至頂邊的距離取黃金比例短邊做為稻草垛的高度。

4、以稻草垛的高度至頂邊的距離取黃金比例短 邊做為堆稻草農夫、農婦的高度。

畫面左右長度黃金比例分割

1、取左右總長度的黃金比例短邊做為堆稻草紅衣農婦的位置。

2、取左右總長度的黃金比例長邊做為堆稻草農夫的位置。

3、取起邊至堆稻草紅衣農婦位置的距離取黃金比例短邊做為哺乳幼嬰婦女及懷中幼嬰的位置。

4、以哺乳幼嬰婦女及懷中幼嬰位置至堆稻草紅衣農婦位置的距離取黃金比例長邊做為在旁哄幼嬰婦女的位置。

5、以堆稻草農夫位置至末端的距離取黃金比例短邊做為牽牛藍衣婦女的位置。

6、以牽牛藍衣婦女位置至端的距離取黃金比例短邊做為拋稻草紅衣婦女的位置。

2007 豐收 193.9*130.3cm Bountiful Harvest

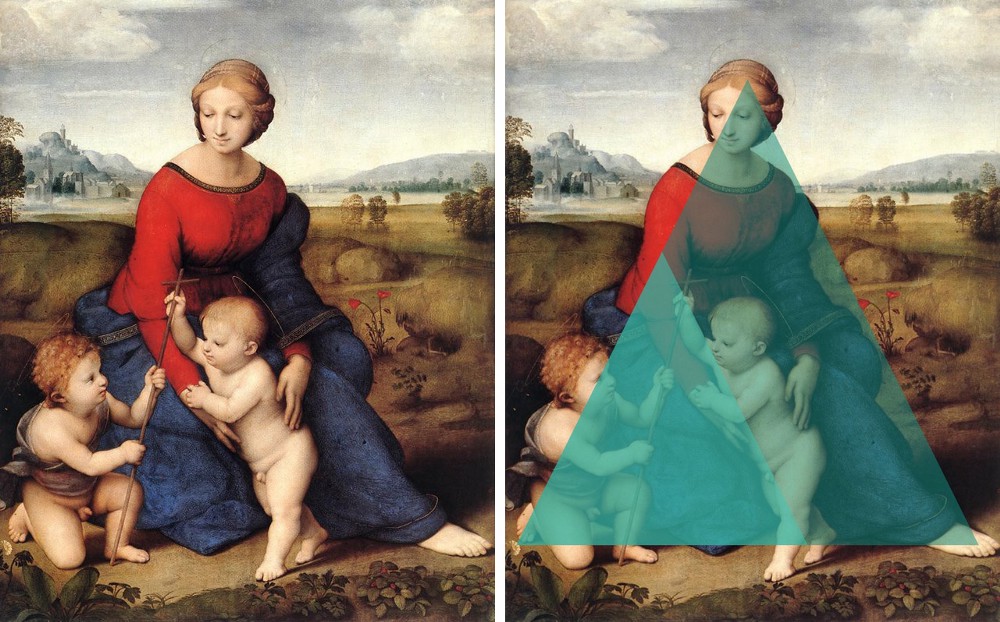

附錄:三角形構圖-拉斐爾·桑蒂(The Alba Madonna)

How to Read Paintings: The Alba Madonna by Raphael

A masterpiece of composition and powerful elegance

The Alba Madonna (c.1510) by Raphael. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Image source Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

I find that the more you look at this painting, The Alba Madonna by Raphael, the more compelling it becomes.

Let your eyes explore the shape and form of the Virgin Mary’s blue cloak, for instance. See how it gently dominates the scene, not only unifying the three figures in the picture by holding them within its folds, but also seeming to rest so naturally around Mary’s form, over her outstretched leg and onto the ground beneath her.

The effect is not only to create a harmonious composition, but also to establish the peace and integrity of the holy family — Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist — in visual form.

Raphael has the somewhat dubious distinction of being called a “perfect” painter. So many of his works have the aspects of serenity and inner harmony that it can be all too easy to stop looking at them with any degree of scrutiny. He was not a painter of mysterious or violent scenes. Instead, his artistic efforts went in search of a different type of mystery — a pursuit of harmonious beauty. Yet it was a search that is no less fascinating.

Detail of ‘The Alba Madonna’ (c.1510) by Raphael. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Image source Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Images of the Virgin Mary and Christ as a young child — otherwise known as the Madonna and Child — have a long history in Western art. The earliest examples can be found in the Christian catacombs in Rome that date as far back as the 3rd century. This painting, made in around 1510, marks one of the great achievements in Renaissance art.

Perhaps what is initially most striking about the Alba Madonna painting its the circular form. This is a so-called “tondo” painting, from the Italian rotondo meaning “round”.

Numerous legends sprung up over the centuries that sought to explain why Raphael painted in the tondo-form. Most of them rehearse the cliche of the itinerant artist moving from place to place, who, thanks to his spontaneity and exceptional talent, was able to paint on anything that came to hand — in this case, a circular panel from a wooden barrel.

In truth, Raphael was a far more considered artist than these stories give him credit for. To have simply grabbed the first piece of wood that came his way was wholly unlikely. In fact, the tondo-form was popular in Florentine painting, and had its roots in Greek antiquity.

Raphael made numerous sketched studies for the Alba Madonna, and these show that the tondo-form was present in his thoughts throughout the planning process.

The sketches also offer a crucial insight into Raphael’s working technique, not least how he worked through various ideas of the composition, looking for ways to interlock the three figures in a rhythmic pattern within the circle.

The Alba Madonna is notable for showing Mary sat on the ground next to a tree stump. This follows the lesser-known tradition in Christian art known as the “Madonna of Humility”, in which images of the Virgin show her sat on the floor or on a low cushion, indicating her humbleness.

Detail of ‘The Alba Madonna’ (c.1510) by Raphael. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Image source Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Raphael worked especially hard to arrange the three figures in a harmonious group, using their line-of-sight to forms an intimate and rhythmic unity. He also learned from artists around him. The upturned gaze of John the Baptist, for example, was a technique common in paintings from Urbino, where Raphael first trained under the artist Perugino.

Composition always played a vital role in Raphael’s work. The precise arrangement of elements in the painted space give his work an inner unity and structural balance. See how, for example, the head of John the Baptist is slightly larger than that of Christ, as a means of balancing out the interplay of looking, and how Jesus holds John’s staff, so physically linking the figures.

Perhaps more than any other artist of his generation, Raphael made use of geometrical shapes in his compositions to elevate his art towards the Renaissance ideal of mathematical harmony. A few year before making the Alba Madonna, Raphael painted the Madonna of the Meadow (Madonna del Prato), also known as the Madonna del Belvedere after the Viennese castle where it hung for many years.

In this work, there is an obvious pyramidal composition. Mary’s head creates the top of a triangle shape; the points of the base are made by her extended right foot and the toes of John the Baptist (bottom-left). There is an inner triangle too, formed between the two children and the shape of Mary’s reaching arm. The unified format gives the work an architectural structure, yet with an inner movement provided by the smaller triangle.

As Raphael’s work grew in maturity, his reliance on the pyramid evolved into a more complex blend of structural elements. In the The Alba Madonna, the triangular composition is still present, but it is allowed to flex with a degree of musicality that is new to Raphael’s work. An elliptical movement between various points of interest creates a beautiful rhythm across the work.

Composition structures of ‘The Alba Madonna’ (c.1510) by Raphael. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Image source Wikimedia Commons (public domain). Edited by author.

The year Raphael made the Alba Madonna, he’d been in Rome for two years. He’d moved there in 1508, summoned by Pope Julius II to decorate the personal apartments in the Vatican. Before Rome, Raphael had based himself in Florence, which was one of the great artistic centres of Italy at the time. Raphael he learned from Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, and in the spirit of the times, imitated many of their techniques in his own work.

The end painting, then, was not arrived at by chance or spontaneous inspiration, but by a careful and thorough working-out. The sketches he made in preparation for the painting also confirm the manner in which Raphael looked to other artists for inspiration, conforming to the prevailing theory of the times in which learning from other artists was seen as essential for creativity and invention. Vasari put is like this: “The most gracious Raphael of Urbino, who, studying the works of old and modern masters, took the best from all, and having gathered them together, enriched the art of painting with that complete perfection.”